Recently I’ve been trying to figure out ways to increase my writing — the amount I complete, publish, and otherwise bring to fruition; the amount of time I spend doing it. For some time now, the answer to the first part has been “zilch,” while the second value has hovered just above “very little.” I spend very little time doing almost no useful (publishable) writing. So we have that out of the way.

Naturally, this is not the state of affairs I prefer.

I enjoy writing and once I get started, I can write happily, sometimes for hours. But the part I steadfastly avoid is getting started. For some reason, I resist writing, or for that matter, any creative effort, whether it’s what I do naturally (write) or something I do because I need to exercise some different skills (arts and crafts, gardening, cooking). Is it because I’m not required to be creative that I can’t engage?

Whatever the reason, I find I’m like the cat who can’t decide what to do next. Faced with too many options, the cat will groom. In a similar position, I plan.

I can plan all day. I love to plan. I make lists like it’s nothing. Think and plan—not do. When it comes to action, I lose my resolve and fall into what DeLillo calls “drift and lethargy.” Oh what a relief that even the great DeLillo has problems with procrastination. But then he has this crazy thing called discipline.

Because it’s relevant and also fun to read, here are a few comments from brilliant and prolific author Don DeLillo on writing and work habits. He writes:

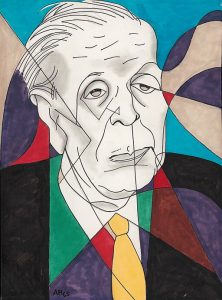

I work in the morning at a manual typewriter. I do about four hours and then go running. This helps me shake off one world and enter another. Trees, birds, drizzle—it’s a nice kind of interlude. Then I work again, later afternoon, for two or three hours. Back into book time, which is transparent—you don’t know it’s passing. No snack food or coffee. No cigarettes—I stopped smoking a long time ago. The space is clear, the house is quiet. A writer takes earnest measures to secure his solitude and then finds endless ways to squander it. Looking out the window, reading random entries in the dictionary. To break the spell I look at a photograph of Borges, a great picture sent to me by the Irish writer Colm Tóibín. The face of Borges against a dark background—Borges fierce, blind, his nostrils gaping, his skin stretched taut, his mouth amazingly vivid; his mouth looks painted; he’s like a shaman painted for visions, and the whole face has a kind of steely rapture. I’ve read Borges of course, although not nearly all of it, and I don’t know anything about the way he worked—but the photograph shows us a writer who did not waste time at the window or anywhere else. So I’ve tried to make him my guide out of lethargy and drift, into the otherworld of magic, art, and divination.”

Don DeLillo, from an interview the Paris Review, 1990s?

How wonderful. I find this statement almost as inspirational as DeLillo finds Borges’ photo. It’s a “guide out of lethargy and drift.”

Inspired by this snippet of DeLillo, I have begun to read Borges finally, after years of wanting to but never being able to remember his name when I was in a bookstore. Or pronounce it, for that matter. His name, the name of this great author, thinker, and student of literature is Jorge Luis Borges. He writes short pieces, often as short as 2-3 pages, with evocative titles and playfully misleading premises. People like to talk about how he writes reviews of imaginary books, which he does, but playful as it seems, it’s so much more than just a game. He’s such a genius at fantasy that after a very short while, the author himself starts to seem fictional too. But returning to imaginary books—why?

(An answer—suppose a book needs to be written, but no one has written it. Why go to the trouble of writing this book when you can just take its existence for granted and comment on it yourself? This is Borges.)

I’m reading Borges and like DeLillo, I find Borges’ face haunting, especially his upward gazing eyes on the Grove Press cover of Ficciones. The silver nitrate-colored oblong that fills most of the front cover portrays Borges in a theater-like space, clearly looking, seeing. But Borges is blind. This black and white screen, this tesseract of potential vision, is a cinema of the mind, faceted beyond the limits of imagination.

I’m inspired by Borges, his writing (what little I’ve read), and the man himself, who emanates mystery and, again quoting DeLillo, opens the door “into the otherworld of magic, art, and divination.” How can you not love this? Eliot would have, T. S. that is, had he read him. (The two were contemporaries.) The reader enraptured, the writer enflamed.

Borges says anything is possible in writing, language, and literature. Anything can be created, interrogated, forced to give up secrets. In like manner, Borges sees writing as a tool to approaching life’s knotty questions, all of them really, from “why are people so messed up” to “life, the universe, and everything.” Borges says that you don’t need thousands of words to do this. From 5 to 5000, it might be enough. The goal is simply to answer the questions.

Moving away from my inspirators, who are only peripheral to this narrative, I know there are a lot of things I’d like to sell, but not here babe. (Every time I turn around, I find I’m shot.)

Why do I mention Malkmus? What does Pavement have to do with my writing practice? Oh, I don’t know, maybe the fact that Malkmus read DeLillo, not just the big sexy books like White Noise and Libra, but the quirky, early stuff like Americana, from

which I feel sure Malkmus plucked the line “there’s no coast of Nebraska” on his band’s own tour de force, Brighten the Corners.

Everything connects.

One day recently, after allowing all the fore-written to ramble through my brain for a sufficient amount of time for it to settle comfortably into my subconscious and simmer, I started to get useful directives. Nothing deep, nothing heavy, man. Just simple, easy things to do. Here’s one.

1. Write every day even if only for 30 minutes. Write every day. Write for 30 minutes, or longer if you want. Write for as long as you want but at least for 30 minutes, no matter what you think the outside world wants of you. Write every day.

Here’s another:

2. Publish this writing somewhere, most practically on a blog or other web site. Your post can be short, very short, indeed. All that’s necessary is that you say something.

And that’s that. Do these two things every day. Do them early and do them with enthusiasm, and you will not go wrong.

Postscript:

Another writer who has inspired me with his description of his work ethic is Ernest Hemingway; chiefly, the bits of avuncular advice on writing that I’ve been able to glean from his early memoir A Moveable Feast. There he writes that he likes to write every day, often in a cafe, out of doors, (the Closerie Des Lilas, most frequently). What makes his approach uniquely useful is the transition from one day to the next. Specifically, he likes to end his sessions with something juicy to get started with the next day1—a sort of “writer’s cliffhanger,” if you will. And so to that end, the next essay in this series will be about the corruption of the narrative. Only I know what I’ll say, but it’ll be good.

1 “I had learned already never to empty the well of my writing, but always to stop when there was still something there in the deep part of the well, and let it refill at night from the springs that fed it.” – Ernest Hemingway, “Une Generation Perdue” from A Moveable Feast, p. 26