I’ve been reading about Genghis Khan and the Mongols recently, for no particular reason, and learning about the years of the Mongol invasions. This was the period during the 13th century when the Mongols were suddenly possessed with something akin to the Messianic spirit, and decided to take over the world. You may think this an exaggeratation, but it really was their intention to take over and rule the entire planet, and they believed, according to the author of the book I’m reading, that their god wanted them to do it. Moreover, they were so completely full of themselves that they actually thought they could. Little things like determined opposition, overreach, and tribal infighting never occurred to them.

So around 1205, the Mongols began their conquest of the world. Genghis Khan started with Siberia before moving on to China. This proved to be slow-going so another contingent of Mongols went west against pretty much everybody else, right through to Bohemia and south through all of the Middle East. It was quite an accomplishment. They took over Central Asia, the Caucasus, Ukraine, and Russia. They captured both the Armenias, the Bulgarians, Persia, Iraq, Turkey, Greece, Syria, and the Levant, including Jerusalem and Antioch.

At the same time, yet another contingent of Mongols took Poland, Finland, something called Livonia —now Latvia and Estonia—as well as all of Eastern Europe. The invaders got as far as Austria before, for some unknown reason, they stopped suddenly and pulled back. For once, France and the Low Countries were not invaded, making this a rare exception in wars of conquest involving Europe. But the Mongols were not done. They continued to take on new targets including India, Tibet, Korea, and even Japan1, although their efforts in these regards were less successful than their takeover of Central Asia and the Middle East. In any event, they managed to rake in a fantastic amount of landmass not to mention loot.

I expect you’re wondering how one little tribe managed to conquer so many nations. It’s easy. They scared the hell out of people. For starters, in the early going they really did “sweep out of Central Asia” as people always describe it, and they were definitely a fearsome, take-no-prisoners bunch of scary dudes. The usual offer was: Submit or die. Or to be more specific, Submit or we’ll destroy your city and kill all your people except for the ones we enslave. People learned very quickly that if they resisted even a little, the Mongols would flatten them, and so after a while, folks would see the Mongols coming and give up immediately. Some of the bigger countries fought back, and they won battles here and there, but eventually, almost all of the Middle Eastern countries had to bow to the Mongol yoke. This meant they had to adapt to the Mongol life-style, pay them tribute, do a fair amount of groveling, and supply them with troops.

Eventually, the Mongols got so comfortable in their role as rulers of the world that they would send out demand letters via emissary, in which they would order the recipient to give up and instruct them on how to behave once they had done so. The first thing a new “client state” had to do was tear down all their defenses. They also had to agree to be looted, all people to be impressed into the Mongol army, and other inconveniences.

Mongol hegemony in the Middle East continued without serious challenge until the 1260, when the Mamluks, who had taken over Egypt some time before, decided not to submit to them. Not only did they not submit, they also killed their messengers, and marched out of their stronghold to meet the Mongols on the field of battle. This was a rare occurrence. Usually, the party to be invaded just cowered in their castles and hoped the Mongols would go away. But in this case the Mamluks were determined and the armies well matched. And lo and behold, the Mamluks won. They took out the top general, leaving his army to scatter in disarray, and a bunch of the Mongols’ slave armies even switched sides. In short it was a rout.

A contemporary commentator summed it up nicely: the Mongols were invincible as long as their opponents feared them. The Mamluks didn’t, and they won. The Mongols expected their enemies to break and run. When they didn’t, it was they themselves who ran.

Sometimes, the enemy seems like the Terminator, impossible to beat. But that’s not necessarily true. In the case of the Mongols, at least some of their success could be attributed to their reputation alone. All they had to do was say boo, really. But then they lost to the Mamluks down in Egypt, and you could almost say it broke their power. They certainly were never quite the same after, and although their raiding and conquering continued, it was never as successful as in the early days before anyone knew who they were.

And so, let that be a lesson to us not to fall for scare tactics, shock and awe, or any of that other PR stuff. Sometimes even the most belligerent of foes aren’t as invincible as they seem. All it takes to beat them is courage and a huge army.

For more on this fascinating topic, there are dozens of books, including the one I’m reading, The Mongol Storm: Making and Breaking Empires in the Medieval Near East by Nicholas Morton.

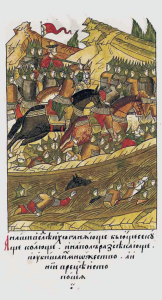

Photo credit: Anonymous Russian manuscript illuminators, 1560-1570s Facial Chronicle (Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan the Terrible) (in 10 volumes: pdf, pdf with translation)Public domain image, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons