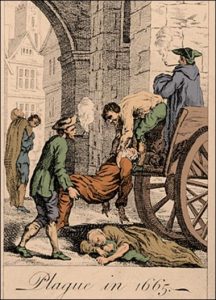

Because I’m a glutton for punishment, I’ve been reading “plague literature,” which is really only interesting if you happen to be going through something comparable as we are now. Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of a Plague Year is just what you’d expect — an account of one year in the life of a Londoner as he navigates the complexities of surviving the Great Plague of 1665.

To begin with the differences, Covid-19 has nothing on the Black Death. Bubonic plague is a gruesome bacterial infection that causes horrible symptoms with a very high chance of mortality. It’s definitely a matter of degree. But it was a pandemic, at least in the British Isles, and despite the long span of years between our two events, there are surprising similarities between “the Plague Year” then and now.

It should also be pointed out that Defoe’s Journal is not a real journal — he was only 5 years old when the events occurred and his book was written over 50 years later. However, as a Londoner born in or near St. Giles, Cripplegate where the plague started, his interest in the subject must have been keen. So although Defoe’s account is well researched, Journal of a Plague Year is what you might call fictionalized fact.

The book begins thusly (cue ominous music):

“It was about the beginning of September 1664, that I, among the rest of my neighbours, heard, in ordinary discourse, that the plague was returned again in Holland.”

Everyone knew what that meant. It meant the plague was coming. When would it come? Where would it strike? Would it come at all? People fretted these questions all fall and into the early winter. Meanwhile, the government immediately met to discuss “ways to prevent its coming over” but, Defoe says, “all was kept very private.” Meanwhile, the plague percolated in the background just as coronavirus did around the world in 2020.

It wasn’t until early December that the first cases emerged in the suburban borough of St. Giles, just south of London. The first statistics were created: “Plague, 2. 1 parish affected.”

Says Defoe, “the people showed a great concern at this, and began to be alarmed all over the town, and the more, because in the last week in December 1664 another man died in the same house, and of the same distemper.”

And then there were no more cases for six weeks.

After this, it became a game of watching the numbers, the so-called Death Lists that each parish issued weekly to report how many people had died and of what. Of course, in the early going, no one wanted to admit they had the plague, so (Defoe theorizes) people lied on the death notices and said it was something else like an accident or spotted fever. But the numbers went up and up, and pretty soon, people couldn’t hide it anymore.

By June, Londoners were pretty convinced they were in for it, and anyone who could escape London for the countryside did so posthaste. Defoe says (backed up by actual diarist Samuel Pepys) that there were so many people evacuating, by horse, cart, post, and on foot, servants and possessions in tow, that it hardly seemed there could be any people left in London to catch the plague. But there were.

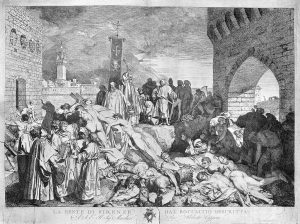

A flood of governmental decrees was issued, in this case from the Lord Mayor of London, aiming at mitigating and relieving the plague. All but essential businesses were closed. Provision was made for the poor and unemployed, of whom there were many. Many new job titles were created such as watchers and dead cart drivers. Most controversially, any household stricken with the plague was ordered “shut up” with all members of the household inside, regardless of their state of health, and kept there under 24 hour armed guard.

You can imagine the distress of families thus locked in together. This is not to say that they were abandoned there to die — they received home food delivery free of charge, medicine and medical assistance, and anything else they needed. They just couldn’t leave the house.

The trouble with this practice was that healthy people anxious to avoid infection were forced to remain in the house with plague victims. This resulted in a great outburst of civil disobedience, which is to say, many people who had been shut up simply escaped, out of back doors and windows, or, if they could get the guard drunk enough, out the front door. While Defoe agreed that it was a good thing to keep plague victims from raving in the streets, he thought it cruel to keep the “sound” in with them, and felt that since so many escaped confinement and ran away taking their contagion with them, it did no good in the end.

It wasn’t until the plague reached its peak in August that people started to realize that apparently healthy people could still transmit the plague. The idea of a symptomless carrier was probably the most frightening to contemporary Londoners. Up to then, they could identify plague victims much as we identify zombies today — they looked horrible and were lurching around. But healthy plague carriers was too much. Many people who had been trying to keep a limited social life going up to that time went right back into isolation.

Defoe goes on at length about the psychology of the people, from nonchalance in the early going to panic when the Plague struck, to abject fear and misery during its height, and finally resolving into resignation and nihilism as it seemed as though none would escape. But then in late September, with weekly numbers approaching 20,000 dead, a strange thing happened. The death rate began to fall. As many as before and more so caught the disease but the numbers of the dead declined. It was, says scientific-minded Defoe, an act of Divine Providence, a reprieve direct from God on high. Today, we might have other postulations.

As for the citizens, their greatest desire was a return to normalcy — to go back to face to face meetings, parties and gatherings, and normal social relations between people. People’s desire to hang out together was so great that restrictions were dropped as soon as the numbers did. This led to many unnecessary deaths, according to Defoe, because people were still dying, just not so many. But clearly man is a social animal and to be deprived of human company was a fate worse than death for many.

Once the plague was over, it took a while for things to return to normal. From a trade standpoint, it was months before any European port would allow English ships to enter. Moreover, the poor and unemployed were generally still poor, but the plague being abated, no one bothered to help them any more.

Nevertheless, the Great Plague gradually ebbed away never to return, and life did finally return to normal. Gone were the dead carts and gruesome sights and sounds of dying people. Gone the open pit graves outside of every church in London, filled to the brim with the bodies of the recently dead. Gone the fear of making a mistake and catching it yourself. It was all over, if not forgotten.

In light of all that had happened, it may have been just as well that the following year, the entire city burned to the ground in The Great Fire of London. The fire may not have killed the plague but it certainly destroyed a lot of plaguey places, giving people a chance to rebuild anew.

A Journal of a Plague Year is a gripping little book that manages to make something quite awful into a surprisingly entertaining read. The details are horrific but there are so many interesting similarities to our own times, that it carries you right along. Readers of today will recognize many elements from this strange and terrible episode in human history.

And so, as we close, I will leave you with the final lines of the novel, a couplet attributed to our fictional narrator, H.T., and of which I will say in advance, may we all be so lucky:

“A dreadful plague in London was

In the year sixty-five,

Which swept an hundred thousand souls

Away; yet I alive!”